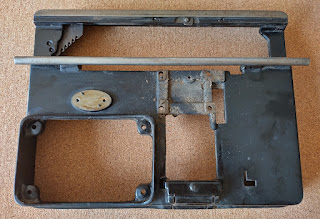

Yet another Mignon, but this one with a serious Zamac-problem. (A small flock of Mignon Modell 4's have been passing by - giving good opportunity to learn how these can look fine and still be completely broken. Also to learn how these come apart - and go together again.)

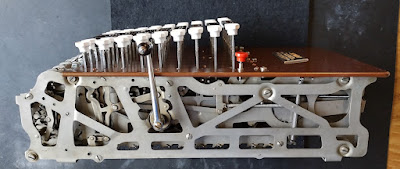

The horizontal bearing on this machine was stuck solid in the cast-iron forked-lever from internal swelling. This meant that this Mignon could not type, as the index then won't budge vertically. When trying to remove this bearing to fix by sanding down, it unfortunately completely crumbled.

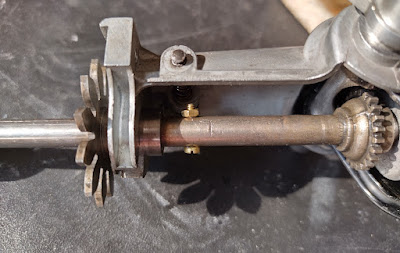

Then the only way to make the Mignon index-typewriter functional again, is to make a new replacement part. The dimensions of the horizontal bearing are metric and fairly standard; it essentially is a tube of 10 mm diameter with 8 mm internal diameter and 80 mm long. It has a flange to fix it to the main cross-casting, a large cut-out to accommodate the gear and one 'internal nail' to lock the rack.

The local DIY-store had 10 mm aluminium tube with 1mm wall-thickness and 2 mm thick strips of aluminium too. One metre lengths of both - to allow for several attempts at making replacement bearings :)

To get the pattern of the cut-out, papper was wrapped around the taped-together original. With a soft pencil, the cut-out was traced, like a brass-rubbing.

The pattern then cut out of the paper and traced onto a length of the aluminium tube. (A bit of extra length to allow clamping without damaging the bearing-surfaces.)

The pattern for the fixing-flange was also sketched and glued to 2 mm thick aluminium. The diameters of the holes are 10 mm (obviously) and 4 mm at a 10 mm pitch. The lug at top is 8 mm wide. This flange should be 3 mm thick. The DIY-store only having 2 mm strip, it'll be doubled to 4 mm.

All material having been marked, then patterns were drilled, sawed and filed. A lot of filing, actually. But then at the end of the filing, there is a replacement horizontal-bearing made out of solid aluminium.

As can perhaps be spotted in the image of the two side-by-side, I made a mistake when glueing the flange in-place on the tube (cyanoacrylate). It is placed ~1.5mm too close to the near edge. Another attempt new-part could be made, but after also shortening the far-end by ~2 mm it's still functional and symmetrical. (Next time I'll measure twice before gluing once.)

At the very bottom of the fixing-flange a ~1.5 mm through hole must be drilled. From the inside, a short nail is driven into this hole. The ~4 mm head of this nail works as a guide for the gear-rack to stay aligned with the gear-wheel. Not an obviously visible feature of the Mignon mechanism, that nail.

The drawn 10 mm tube is a perfect fit for the cast-iron fork-lever, and allows the mechanism of the Mignon to again swivel back-n-forth for the vertical axis.

Also replacing the pin in this machine's shaft with a brass M2 bolt and nut (just visible), this Mignon index typewriter is again fully functional. Still not a speedy machine, but it writes again. To finish it off, the lettering of the ruler was touched-up and the machine given an overall polish.

A fine machine. (Still wish that they hadn't used Zamac!)